Our Town, Revisited

Act One – Daily Life

I first met Bob and Tia in a most unexpected way. It was the early 1990s, and I was struggling with persistent back pain. Searching for relief, I booked a session with a massage therapist named Jodie Curro. As fate would have it, Jodie was married to a Milwaukee jazz pianist named Dan Dance—a name I’d seen around town and, admittedly, had assumed was a corny stage name. Turns out, it was his real name.

Jodie came out to see me play at a local club and after the show she said, “you sound a lot like Bob Rebholz.” To which I responded “who?” Not long after, I met Dan in person. When he discovered I played saxophone and EWI (Electronic Wind Instrument), he mentioned that a friend of his, Bob, also played EWI and was looking for someone with technical know-how. I had already spent a good deal of time tinkering with those early Akai EWIs, developing workarounds for their many foibles.

Interestingly, Bob had once been engaged to Dan’s sister. Before long, I got a call—an actual landline call—from Bob. He needed help getting his EWI back into playable shape. I worked on the instrument, and somewhere along the way, our conversations evolved from purely technical to genuinely friendly.

The exact sequence of events has faded, but I remember mentioning during one of our chats that I was planning a trip to Mexico. Without hesitation, Bob recommended a place called “Kailum,” speaking about it with a kind of reverence. He described it as a hidden enclave unlike anywhere.

I’m not sure what possessed me but upon hearing his description I blurted out, “Maybe you’d like to join us there?” It was an impulsive invitation—especially strange, considering I’d never met this man or his wife. Equally strange was his response: he said he thought that sounded like a wonderful idea.

And so it came to pass that I met Bob and Tia for the first time in person at the Cancun airport. From there, we shared a week that now lives in empyrean memory—days at Kailum shaded by palm fronds and salt air, punctuated by wanderings to ancient Mayan ruins and the cool, blue hush of cenotes where we snorkeled into the vivid and warm waters. It was the kind of serendipitous beginning that feels, in hindsight, like it was destined to happen.

Back then, Kailum was nestled in what is now the sprawling tourist zone of Playa del Carmen—but at the time, it was utterly off the map. Untouched. Raw. The place consisted of perhaps twenty luxurious palapas tucked on the sand between sea and jungle. An oasis in a landscape still wild and whispering with possibility. Crisp linens on a king size bed were made up daily and your sand floor was raked smooth. There was no electricity. No shoes. Glowing brass lanterns guided you to the gourmet kitchen where four meals were prepared daily by a decorated executive chef transplanted from Denver, Colorado.

You helped yourself to drinks at the honor bar, nudging a simple peg along a sun-worn wooden board—each move a gentle marker of time well spent. When it came time to leave, you paid not just for the spirits poured, but for the memory of a slower, simpler world that had briefly welcomed you in.

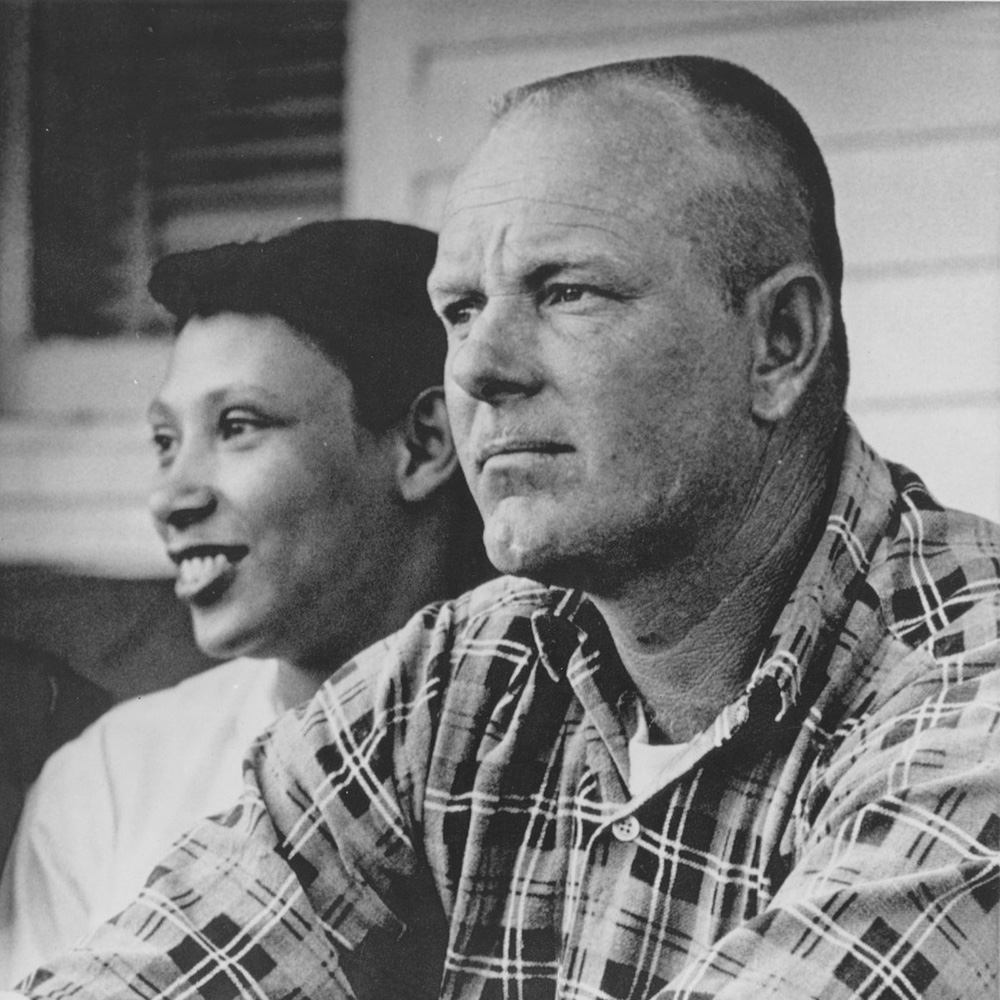

As the days of that that sun-drenched week unfolded, a friendship quietly took root—firm, effortless, and lasting. There was something uncanny about Bob, a man ten years my senior who nevertheless felt like a reflection of myself in a slightly older mirror. But it wasn’t just Bob. His wife, Tia, left an equally vivid impression—a delightful enigma of a woman, eccentric and luminous, a vessel brimming with generous spirit.

Our first outing set the tone. We piled into Bob’s modest VW rental, beach towels and curiosity in tow. Before Tia joined us, Bob gave a knowing glance and said, almost ceremonially, “Tia will get in and immediately spend ten minutes adjusting all the vents.” And true to form, she did—methodically, compulsively, as if orchestrating the airflow of the universe. It became an enduring inside joke; one wrapped not in mockery but in admiration. A quiet tribute to her singularity. The last time I saw her I smiled silently in the back seat as she got in and repeated the exercise – a full thirty years later.

Tia had that rare magic: snarky and sincere in equal measure, unpredictable in the most endearing ways. By the end of that week, I didn’t just feel the warmth of new companionship—I knew, with quiet certainty, that I had found something enduring. A friendship that would stretch far beyond those white sand shores.

…

It’s a quiet morning in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, in the year 1901. The Stage Manager steps onto the empty stage—part narrator, part guide, part philosopher—and begins to gently conjure the world of the play you are about to watch. He introduces us to the town not with spectacle, but with stillness: the local newspaper editor, the milkman, the constable making his rounds. Life, here, is humble and habitual.

We meet the Gibbs and Webb families; neighbors whose lives unfold side-by-side in the quiet cadence of small-town life. Dr. Gibbs returns from delivering twins. Mrs. Webb calls her children to breakfast. Time ambles forward with the simplicity of breakfast tables, schoolbooks, and string beans shelled on front porches.

Nothing much of note happens. We see the gentle rhythms of the town: the morning rush, school, afternoon strolls, and quiet evenings. There are small but telling moments—Emily receiving praise for her intelligence, George being gently nudged toward responsibility. And through it all, playwright Thornton Wilder weaves the beginnings of a tender connection between the two, just beginning to sense one another in a new light.

Act Two – Love & Marriage

A handful of years went by and despite Tia and Bob living in Denver, I saw them regularly. Bob’s family lived in Milwaukee and that brought them my way at least once a year. My penchant for snowboarding brought me their way. I often stayed at their home on the edge of sprawling Denver.

If you’ve followed these essays—or if you know me beyond the page—you’ve heard whispers of the storm I weathered in 1997. The divorce. I’ve skimmed along its surface, hinting at the fracture without exploring its depths. But those who were beside me then know the shape of it, the weight. Tia, in particular, became something of a lighthouse—steady, wise, and clear-eyed in a moment when I couldn’t see past the wreckage, much of which I created.

God knows, I needed that. Because the truth is, we often become the architects of our own undoing. And sometimes that’s necessary. I had built a life like a painting—carefully composed, all light and balance—but I wasn’t really in it. I was outside the frame, curating a version of living rather than living itself. In the end, it all had to come down. Only then could something real begin. That’s decades of hindsight talking.

Bob is an extremely accomplished saxophone player. He’s played with many renown artists and he’s a joy to listen to. He’s also a truly talented teacher. He has a much deeper understanding of music theory than I. I’ve had lots of formal training including an associate’s degree in music performance, but much of it just didn’t take. Bob not only understands this stuff, he makes that crucial connection between the academic understanding of music and its artful performance. He never sounds like a method book. Every time I’ve visited, I come away with some very useful nugget that Bob teaches me. His wit is also boundless. I’m sure our endless conversations about saxophones, mouthpieces, reeds and so on have bored our companions to tears, but I’ve sure enjoyed them.

In Bob and Tia, love wasn’t performative. It was practiced—steady, graceful, and quietly luminous. You don’t often see that kind of thing, but when you do, it catches the light.

Tia was previously married to a drummer. And get this –one of Bob’s best friends and musical compatriots. He still plays with this guy regularly. Tia has a daughter from that first marriage and like most kids of divorce, she came and went. A backpack kid. I once stayed in her room, which exuded a unique, emo personality.

In 1997 Bob and Tia had a son of their own, Ryder. He was a precocious little guy who resembled his father in both appearance and gift. I mostly tracked Ryder’s life through social media but was also able to visit with him when I’d see the Rebholz family. One video of Ryder really stands out in my mind. A young boy seated at a piano bench wearing pants that he’ll “grow into,” plays beautifully through a jazz standard including improvising well beyond his years. He finishes and flashes a coquettish smile off camera. His proud father looks on. I got to witness a similar scene at their house as he and Bob sat side-by-side on the piano bench working their way through a few songs together.

As Ryder edged into adolescence, the changes came quietly at first—small withdrawals, a fading of once-cherished passions like music. In time, the signs grew more apparent: a drift into idle distractions, a sense of something unspoken shifting beneath the surface. The specifics matter less—many young people slog through the uneasy passage into adulthood—but what stayed with me was his parent’s response.

“I’m just going to keep throwing love at it,” Bob said, with a quiet, aching resolve.

It was a simple phrase, and yet, one that eludes so many parents. A kind of vow—tender but stubborn.

One place where Ryder found solace—where something like joy seemed to flicker—was on a skateboard. It’s a pursuit close to my heart. As a kid growing up in a deeply dysfunctional home, then shuffled off to a boarding school ruled by rigid expectations, skateboarding became my escape hatch. My reprieve. It got me through many tough times.

There are a thousand reasons I love it. Skateboarding belongs to no one and everyone. There are no teams, no tryouts, no whistles or uniforms—just you and the board. You move at your own pace, on your own terms. It is something you can do anywhere at any time. It’s supported by a judgment-free community.

It teaches you things that matter. That failure isn’t something to fear, but a necessary step. That persistence, not perfection, is what carries you forward. But more than anything, it’s the rhythm of it I’ve always loved—the way it flows, how the body and board respond to gravity and momentum. There’s something in that fluidity that calms my mind despite punishing my body. I still skate today, at 62. Not for tricks or speed, but for the quiet it brings and to recapture those childhood moments. Seeing Ryder find even a little of that same peace was heartening.

…

“Three years have gone by. Yes, the sun’s come up over a thousand times. Some babies that weren’t even born before have begun talking regular sentences already; and a number of people who thought they were right young and spry have noticed that they can’t bound up a flight of stairs like they used to, without their heart fluttering a little. All that can happen in a thousand days.”

In a tender moment at the local soda fountain over strawberry ice-cream sodas, George and Emily first truly acknowledge their feelings for each other. They awkwardly navigate their emotions, with Emily expressing disappointment in George’s recent arrogance and George, humbled, deciding not to go away to agricultural college, choosing instead to stay in Grover’s Corners to pursue a life with her.

“I’m celebrating because I’ve got a friend who tells me all the things that ought to be told me,” George says.

After this glimpse into their emotional turning point, the scene shifts to the day of their wedding. We see the preparations in each home.

“I don’t know why on earth I should be crying. I suppose there’s nothing to cry about. It came over me at breakfast this morning; there was Emily eating her breakfast as she’s done for seventeen years and now, she’s going off to eat it in someone else’s house,” Emily’s father huffs.

There’s a subtle tension in the air—nervousness, even panic, felt by both George and Emily. Their parents also wrestle with letting go. Mr. Webb, in a touching moment, offers George awkward advice, while Mrs. Gibbs and Mrs. Webb both show quiet signs of maternal sorrow.

Act two fades to black as George and Emily exchange marriage vows.

…

Act Three – Eternity

The lights dim to black as the Choir’s singing fades and eight ladder-back chairs are placed in two openly spaced rows facing the audience. Once they are in place, the actors enter and take their places. The front row contains an empty chair; then Mrs. Gibbs and Simon Stimson. The second row contains Mrs. Soames and Wally Webb. The Stage Manager enters as the lights come up slowly.

A conversation begins among those seated in the chairs and soon we realize these are the dead of Grover’s Corners.

“Nine years have gone by, friends… Gradual changes in Grover’s Corners. Horses are getting rarer. Farmers coming into town in Fords. Everybody locks their house doors now at night. Ain’t been any burglars in town yet, but everybody’s heard about ’em. You’d be surprised, though; on the whole, things don’t change much around here.”

“Now there are some things we all know, but we don’t take’m out and look at’m very often. We all know that something is eternal…everybody knows in their bones that something is eternal, and that something has to do with human beings. There’s something way down deep that’s eternal about every human being.”

Emily has died in childbirth. Her chair in the graveyard awaits. But she’s allowed to go back to relive one day in her life from the beyond. She chooses her sixteenth birthday. She sees her mother stressing over the details of her cake and other preparations and tries to stop her, ties to intervene to tell her to savor every seemingly trivial moment. But she is only viewing a replay and cannot communicate with the living.

“Mama, I’m here. I’m grown up. I love you all! Everything. I can’t look at everything hard enough. Good morning, Mama!”

“Oh, Mama, just look at me one minute as though you really saw me. Mama, fourteen years have gone by. I’m dead. You’re a grandmother, Mama. I married George Gibbs, Mama. Wally’s dead, too. Mama, his appendix burst on a camping trip to North Conway. We felt just terrible about it—don’t you remember? But, just for a moment now we’re all together. Mama, just for a moment we’re happy. Let’s look at one another.”

“I can’t. I can’t go on. It goes so fast. We don’t have time to look at one another.”

“Goodbye, Goodbye, world. Goodbye, Grover’s Corners…Mama and Papa. Goodbye to clocks ticking…and Mama’s sunflowers. And food and coffee. And new, ironed dresses and hot baths…and sleeping and waking up. Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you. Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it…every, every minute?”

“They don’t understand, do they?”

…

On Sunday, June 1 I was setting up at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas for the last of an exhausting weekend of performances. We had played in San Diego the night before. Scattered in the usual pre-show chaos, amid the din of soundcheck, my phone rang.

Tia.

There was a prescient pang in my heart. One of those rare moments when your body knows something your mind hasn’t caught up to. I somehow felt something was wrong. This wasn’t a social call. I couldn’t answer as it was very loud, but a few minutes later I listened to the voicemail. I could tell by the disembodied voice that something was gravely wrong. Something must have happened to Bob, I thought.

I called Tia back. “I don’t like the sound of your voice,” I said. “There’s good reason for that,” she replied. “Ryder was in an accident last night…Clay, he was killed.” The world seemed to slow, as if the air had thickened around me. My throat closed. Her words hung there—heavy, surreal—suspended in the dry air. My chest tightened; I couldn’t quite breathe. Silent tears began to roll. I sputtered through condolences overwhelmed by feelings helplessness.

As the conversation went on, I realized: Tia was comforting me. Even in her own moment of devastation, she held me up.

It happens every day to someone. It’s the call or in this case the midnight knock at the door that every parent fears most.

Everything I was doing immediately felt trivial. Because it was. And for weeks I felt that way. This tragedy invaded my daily thoughts and activity like an insidious weed in an otherwise lush and verdant garden. Until one night I heard in my head the assuring voice of my father, “Our Town,” he said.

Epilogue

I first became acquainted with Thornton Wilder’s play “Our Town” through the messages my father delivered. He helped start an organization called Sports World Ministries which brought short Christian chapel services to the visiting team locker room or a pre-game hotel. It began in NFL football but quickly was expanded to Major League Baseball. As a young child I would accompany my father to these and hear him speak the gospel to Reggie Jackson, Yoggi Berra, Bart Starr, OJ Simpson and the like.

He would frequently conclude with one of two vignettes. The first was the true story of Frank Buncom. A three-time all-star, Buncom played for seven seasons with the San Diego Chargers and the Cincinnati Bengals.

Buncom was slated to be a starter for the 1969 Bengals. The evening before the opening game of the season against the Miami Dolphins he attended a chapel service conducted by my father and was confronted with the message of grace, the message of salvation. Afterwards as the team filed out, he told my father he wanted to think about it for a while. But he died of a pulmonary embolism in his sleep that night never making the season opener in the morning.

The second was the story of young Emily from “Our Town,” a play I had never seen.

My father’s message was the same with each story – life is transient, and we fail to understand that the trivial moments are indeed the very thread that weaves the fabric of our lives. That we rarely understand the importance of the moments we’re living.

We can’t put off for tomorrow, ignoring the impermanence of life. I can’t make sense of this suffering. But I have decided two things. To take Emily’s advice and savor every trivial moment. And second, to take Bob’s and in all things to “throw love at it.”

In loving memory: Ryder Rebholz 1997-2025